Church groups weave a web of support for refugees in Lebanon

By Laure Delacloche, CNEWA

The people living at a refugee camp in Dbayeh, Lebanon, were barely keeping their heads above water when a full-scale war between Israel and Hezbollah, a political party and Shiite militia based in southern Lebanon, was unleashed in mid-September.

A day after Israel began bombing Gaza in retaliation for the Hamas attacks on 7 October 2023, the Iran-backed militia of Hezbollah launched missiles into northern Israel in support of Hamas. Exchange of fire between Israel and Hezbollah ensued.

The conflict escalated drastically with Israel’s launch of a full-scale war on Lebanon on 23 September and a ground invasion that followed on 1 October. By the end of October, Israel’s bombardments in southern Lebanon, the Bekaa Valley and the suburbs of Beirut had killed more than 2,600 people and internally displaced about 1.2 million — about a fifth of the country’s total population.

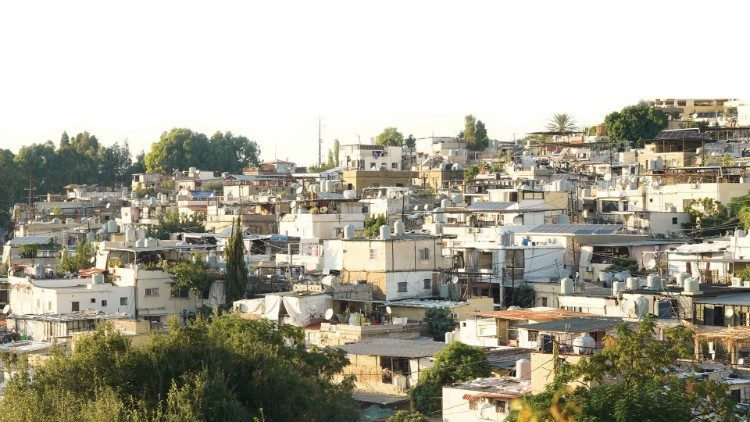

By early October, 100 internally displaced families had arrived at Dbayeh camp seeking shelter within a setting already stretched to the breaking point. Located about eight miles north of Beirut, the camp in Dbayeh was established to shelter Christian Palestinian refugees expelled from the Galilee.

“We were not prepared to receive them,” says Sister Magdalena Smet, P.S.N. “The conflict escalated so quickly.”

Sister Magda, as she is affectionately known at the camp, is a member of the Little Sisters of Nazareth, a Belgian community of religious women who have been serving the camp since 1987. The three Little Sisters currently working there are at the heart of the response to this latest hardship.

“The families are in need of everything: mattresses, clothes, food, covers,” she says. “We have to count on the generosity and hospitality of people who already have very little.”

In Dbayeh camp, as in most of Lebanon, solidarity with the displaced was immediate.

“I gave my office and my house to three families, and we are using the church hall to organize the supplies and food distribution,” says the Fr. Joseph Raffoul, a Melkite Greek Catholic priest who serves the camp’s parish of St. George.

Rita Ghattas, a Christian Palestinian, says “the situation is stressful.” She was born and raised at the camp, as was her husband, Bassel, and their 15-year-old daughter, Reem.

Bassel’s father was 14 when he was expelled from his village, al Bassa, in the Acre subdistrict of then Mandatory Palestine during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war. The Israeli expulsion of more than 700,000 Palestinians from their villages at that time is called the Nakba, which means “catastrophe” in Arabic. An estimated 15,000 Palestinians and 6,000 Israelis were also killed in that war.

In 1949, Pope Pius XII established Pontifical Mission for Palestine to channel Catholic aid to these Palestinian refugees, entrusting its leadership, administration and direction to Catholic Near East Welfare Association.

The Dbayeh camp was formally established in 1956, on the land of the Maronite Monastery of St. Joseph, where years earlier the monks had set up a tent camp in response to the crisis. The United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) and CNEWA-Pontifical Mission collaborated to replace the tents with one-room shelters.

Bassel’s father eventually took refuge at Dbayeh camp, which over the years has received Syrian refugees and Lebanese displaced by conflict. The Ghattas family is not the only Palestinian family to be living at the camp — originally intended to be a temporary solution — for three successive generations. Prior to the current war, the camp was home to about 610 families — 264 Palestinian families, 271 Lebanese families and 75 Syrian families.

Gerasimos Tsourapas, a professor of international relations at the University of Glasgow, Scotland, explains why the camp has become a permanent home for Palestinian refugees.

Post-World War II nations realized the need for an independent global system “to manage both labor and forced migration, in order for the atrocities of the first half of the century not to be repeated,” he says.

“A global refugee regime emerged, the United Nations and several agencies were created,” he says. “At the heart of this global refugee regime lies the principle to protect the vulnerable.”

An important document in this global effort is the 1951 Refugee Convention, which “outlines the basic minimum standards for the treatment of refugees, including the right to housing, work and education … so they can lead a dignified and independent life,” according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

The UNHCR serves as the “guardian” of the convention and works with signatory states to ensure the rights of refugees are protected. However, Lebanon is not a party to it.

“The global refugee regime has been unable to provide these groups with adequate protection” and host countries continue to carry the main responsibility for their well-being, says Mr. Tsourapas.

According to UNRWA, 45 percent of the estimated 250,000 Palestinian refugees residing in Lebanon as of March 2023 live in the country’s 12 recognized Palestinian refugee camps and experience various forms of discrimination in the law.

Lebanon imposes employment restrictions that prevent Palestinian refugees from working in 70 professions, including as engineers, doctors or lawyers. They are denied the right to own property. They are also forbidden from building additional floors to their housing in the camp to increase their living space.

Lebanon’s economic crisis, exacerbated since its banking collapse after the August 2020 port explosion, has compounded these challenges. In March 2023, 80 percent of Palestinian refugees in Lebanon were living below the country’s poverty line, which stands at $91.60 per month, according to the World Bank. Lebanon’s average monthly income in 2023 was about $122.

While the vast majority of Palestinians in Lebanon are Sunni, the Dbayeh camp hosts majority Christians.

“The Christian refugees are in a different situation than the Muslim ones,” says Marie Kortam, a sociologist and associate researcher at the French Institute of the Near East in Beirut.

In general, the socioeconomic situation of the Christians and the Sunni Muslim Palestinians is similar.

“They face the same restrictions when it comes to accessing the job market, unless they work with religious organizations,” she says. “What is projected onto the Christians is an image of modernity.”

“The solidarity is also stronger, because Christian Palestinians are a small community in comparison with Sunni Palestinians. Some of [the Christians] were granted Lebanese citizenship, especially in Dbayeh camp, in 1991, for electoral purposes,” she says.

Lebanon is a confessional state where elected representatives are religiously affiliated, and where it is common that access to social services or employment is granted in exchange of political loyalty.

A civil committee serves as the camp’s coordinating body and organizes humanitarian aid for residents. Elias Habib, the committee director, says Dbayeh is “different” from other Palestinian camps “because we have to take charge of ourselves, because we have very few UNRWA services.”

Church-run groups, such as CNEWA-Pontifical Mission, which has been present at the camp since its beginnings, and the Little Sisters of Nazareth help to fill the gaps.

The UNRWA-run school at the camp, which was built by CNEWA-Pontifical Mission, was destroyed in 1978 during Lebanon’s civil war, and a new UNRWA school built off-site after the war was closed in 2013 due to low enrollment. The camp has not had a school since, despite UNRWA’s mandate to provide health care and education.

“The public schools give priority to Lebanese students, and then to Syrians, before accepting Palestinians,” says Sister Magda. “Our Palestinian students are pushed toward expensive private schools. This year the tuition fees have doubled; it costs on average $2,500 per year.”

The Little Sisters help coordinate tuition assistance for Palestinian children, since tuition is unaffordable for their families.

“Without Sister Magda, we cannot do anything,” says Ms. Ghattas, whose daughter, Reem, benefits from Sister Magda’s coordination efforts. At the start of the school year, the family received $250 in tuition assistance from CNEWA-Pontifical Mission.

However, the onset of full-scale war between Israel and Hezbollah has required the sisters to redirect their time and resources from the education of 150 Palestinian children to emergency aid.

The camp’s ecumenical Joint Christian Committee for Social Service also covers a portion of enrollment. Its two-story center at the camp offers homework support, vocational training, remedial classes and children’s activities, including a summer camp. The camp’s sports facilities welcome about 150 children, aged 7-17, for soccer and basketball.

Reem, with her hair in a bun and her socks pulled high, says “playing soccer is an escape from everything.”

Lebanon hosts an estimated 1.5 million Syrian refugees.

Massab Alawi, his wife, Hala, and their five children are among 75 Syrian families residing at Dbayeh camp. They fled the civil war in Syria in 2012 and found refuge in a coastal town north of Beirut. However, their children were unable to attend school for two years.

Moving to Dbayeh provided their children with the rare opportunity to benefit from the remedial classes offered by the Joint Christian Committee for 75 Syrian students, whose education was disrupted by the civil war.

“The Syrians are, compared with the Palestinians, doing better,” says Mr. Habib, who also heads the Joint Christian Committee. “Many of them can visit their families in Syria, and they know the war will end one day.”

Lebanon has seen increasingly xenophobic public discourse around the presence of Syrian refugees, but the Alawi family says they feel accepted at the camp.

In the camp, the tension lies elsewhere. The push and pull of influences tied to Christian and Palestinian political parties simmers below the surface. However, the coexistence of Syrians, Lebanese and Palestinians is “going as well as it can,” says Mr. Habib.

Lebanon’s ongoing economic crisis, ranked among the top economic crises worldwide since the mid-19th century by the World Bank, has exacerbated the health care challenges at the camp.

UNRWA runs a dispensary two days a week. A dispensary funded by St. Elizabeth University of Health and Social Work in Slovakia since 2014, where dozens of Lebanese health care workers run volunteer consultations, has been operating five days a week.

“If we need something, we come here directly,” says Rachel Halawi, a Lebanese mother of three.

Each month on average, 650 people visit the dispensary and 1,000 home visits take place. The dispensary covers 50 percent of the costs of the medicines and medical appointments.

Cardiologist Elie Sakr, who heads the dispensary, says the health of camp residents “is worse than 10 years ago.”

He claims the economic crisis “reinforced people’s sedentary life, which generates stress, which in turn generates low immunity, heart attacks, and so on.” The most prevalent illnesses are hypertension, diabetes, kidney, heart, prostate problems and cancer.

“With the same risk factors, people in the camp are [still] in better health than people outside the camp, as the latter have more restricted access to medicines,” says Dr. Sakr, referring to World Bank statistics that indicate 95 percent of households living below the poverty line in Lebanon cannot access medicines they need on a regular basis.

The Little Sisters help to cover health care bills for residents. However, they expect the wave of internally displaced people from southern Lebanon to stretch their meager resources further.

“We will share what we have. God will not let us down,” says Sister Magda.

Psychologist Hala Imad has been volunteering at the camp since 2016. She says the compounded crises and restricted opportunities for camp residents take a toll on mental health.

“Everyone suffers, it is systemic,” she says. “The very camp settings, the overcrowding, are weighing on people.”

Ms. Imad says she sees a prevalence of depression among the residents, noting how the trauma and the tragedy of the refugee experience has been passed on from one generation of residents to the next.

“This is transgenerational,” she says.

“It is very hard,” says Mr. Habib. “We are marginalized. People worry about their children’s future.”

“The hardest aspect of our work in the camp,” says Sister Magda, “is that it is akin to carrying the cross and never reaching the light or the resurrection.”

This article was originally published in ONE, the magazine of Catholic Near East Welfare Association (CNEWA). All rights reserved. Unauthorized republication by third parties is not permitted.

Thank you for reading our article. You can keep up-to-date by subscribing to our daily newsletter. Just click here